Food in Little India Singapore is a flavor-packed journey through rich spices, sizzling street eats, and legendary dishes you won’t find anywhere else.

Little India is one of my favorite parts of Singapore because it’s not a tourist attraction. When you visit and eat in restaurants you’re sitting with local people.

But in order to celebrate it, it’s important to understand Singapore’s history and why Little India exists today.

British colonization shaped much of Singapore’s history, including Little India. In 1822, Sir Stamford Raffles created ethnic enclaves to control the population through segregation.

Although some moved into Chinatown, Indians couldn’t live in European areas. Most early Indian residents were Tamil laborers from South India.

The British brought many Indians to Singapore as indentured workers. They worked on construction sites and cleaned the streets.

Others came as traders, money lenders and shopkeepers. Many worked with cattle, which is why you’ll find the best Indian food near the old cattle trading area.

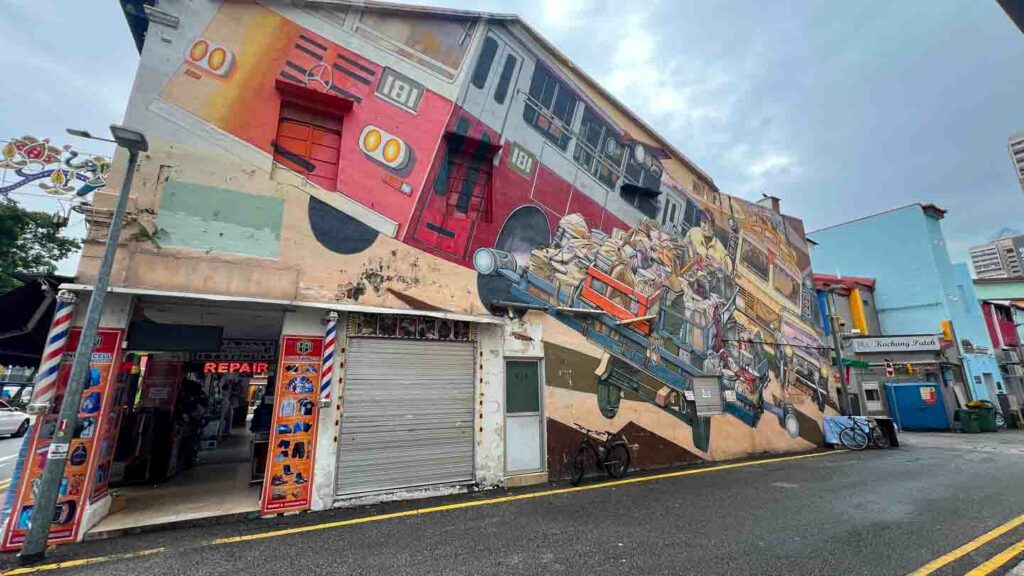

By the 1840s, the area buzzed with Indian businesses. Buffalo Road became the center of the cattle trade. The workers lived in shophouses, while wealthier Indians built temples.

Today, these temples still stand among the restaurants and shops.

The Story of Food in Little India Singapore

Singapore’s Indian food is different from what you’ll find in Chennai or Mumbai. The early Tamil workers adapted their recipes.

They used local ingredients when they couldn’t find Indian ones. Chinese and Malay flavors mixed in too.

The food here is also different from other Little India neighborhoods around the world. Take Vancouver’s Little India – their food stays close to North Indian styles.

But Singapore’s versions changed more. Cooks here created new dishes that don’t exist in India.

Many Singapore Indian dishes came from different groups working together. Chinese workers ate at Indian stalls. Malay ingredients found their way into Indian kitchens.

The result? Unique foods like Fish Head Curry and Indian Rojak.

15 Things to Eat in Little India

Pani Puri

Street vendors from Mumbai introduced pani puri to Singapore. The local version uses sweeter tamarind sauce.

The water (pani) has more mint and less spice than Indian versions. Some places add green mango – a Southeast Asian twist.

Local cooks make the puris smaller. They’re easier to eat in Singapore’s hot weather. The potato filling often includes sweet potatoes, which isn’t common in India.

Moghul Sweet Shop: 48 Serangoon Rd, inside Little India Arcade

Fish Head Curry

This dish shows how Singapore creates new foods. In 1949, an Indian restaurant owner wanted to please his Chinese customers.

Chinese people love fish head. Tamil cooks like curry. The combination became a Singapore classic.

The curry sauce is different from Indian versions. It’s more sour from tamarind and has coconut milk like Malay curries. Indian curry would never use a whole fish head.

The Banana Leaf Apolo: 54 Race Course Rd

Masala Thosai

Tamil workers brought thosai to Singapore. The original was plain, but local cooks added the potato filling.

Singapore’s version is bigger and crispier than South Indian thosai and could easily feed two people. The coconut chutney is sweeter here too.

Kamala Restaurant: Serangoon Rd, outside Tekka Centre

Chapati with Mutton Keema

North Indian workers introduced chapati to Singapore. The local version is thinner than Indian chapati. Singapore’s keema uses more garlic and local spices.

Some cooks add soy sauce – a Chinese touch.

Azmi Restaurant: 2 Dalhousie Lane

Roti Prata

Although I ate this at a South Indian restaurant in Singapore. Singapore’s prata is closer to the Indonesian and Malaysia roti canai than Indian paratha.

Indian paratha is usually thicker, can be stuffed with fillings like potatoes or paneer and cooked with ghee on a tawa.

Singapore’s prata, much like Malaysia’s roti canai, is thinner, flakier, and stretched until almost translucent.

It’s fried on a griddle, often with oil or margarine, and served with curry or sugar.

The doughs are similar — flour, water, and fat — but prata dough gets stretched and folded repeatedly, creating that crispy, layered texture.

Indian paratha focuses more on the filling, while prata highlights the dough.

And here the curry is uniquely Singaporean, much less spicy than Indian curry. Or maybe they just gave the mild version to me!

Where to Eat Prata: Victory Restaurant: 701 N Bridge Rd, #701, Singapore 198677

Singapore’s Chinatown

Tulang Merah

This dish was born in Singapore’s Malay-Indian community. It doesn’t exist in India. Cooks use mutton bones that meat shops would throw away. The red color comes from ginger and chillies.

Workers created it during hard times. They couldn’t afford meat but found bones were tasty. The dish shows how people adapted to survive. Now it’s a popular street food.

Haji Kadir Food Chains: Tekka Centre, 665 Buffalo Rd, #01-297

Biryani

Singapore’s biryani looks different from Indian versions. The rice is more yellow from extra turmeric.

In India, biryani changes by region. But Singapore made its own style. Local cooks use more coconut milk and pandan leaves.

The meat gets cooked separately here. In India, it cooks with the rice. Some places serve it on banana leaves – a South Indian tradition. The spice mix is milder to suit local tastes.

Komala Vilas: 76 Serangoon Rd

Vegetarian Thali

Tamil workers created Singapore’s thali style. It has fewer items than an Indian thali but bigger portions.

The curries are less oily than Indian versions. Local vegetables like water spinach often appear.

Each thali includes Chinese-influenced dishes too. You might find stir-fried vegetables with Indian spices. The dhal (lentils) is thicker here than in India.

Madras New Woodlands: 14 Upper Dickson Rd

Indian Rojak

This dish shows how different cultures mix in Singapore. Indian Muslims combined Chinese fritters with Indian spices. The peanut sauce comes from Javanese cooking. You won’t find this anywhere in India.

Known as rujak in Indonesia, the dish is originally from Java island and has so many versions in Indonesia. It’s also available in Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei.

The name ‘rojak’ means ‘mixed’ in Malay. Each seller has a secret sauce recipe. Some add prawn paste – a Chinese ingredient that makes it unique to Singapore.

Al Mahboob Rojak: 7 & 9 Kensington Park Rd, Serangoon Garden

Murtabak

This dish traveled from Yemen to India to Singapore. It’s one of the most popular street foods in Indonesia, where it’s known as martabak.

The local version is huge compared to Middle Eastern ones. Singapore cooks add extra eggs and local spices. The dough is stretched thinner than Indian murtabak.

Muslim-Indian traders brought murtabak here in the 1930s. They set up stalls near the ports. Today’s versions include modern fillings like cheese – something you won’t find in India.

Zam Zam Singapore: 697-699 North Bridge Rd

Tandoori Chicken

British soldiers who served in India brought tandoori chicken to Singapore. Early cooks used electric ovens because clay ovens were hard to find.

Today’s version is less spicy than North Indian tandoori.

The marinade includes local ingredients like lemongrass. Singapore’s humidity affects how the marinade works. Cooks adjusted their recipes to get the same smoky taste in different weather.

Khansama Tandoori Restaurant: 166 Serangoon Road

Breakfasts in Singapore

Putu Mayam

This Tamil breakfast food changed in Singapore. The rice noodles are thinner than Indian versions. Local palm sugar (gula melaka) replaces Indian jaggery.

The coconut is always fresh – a Southeast Asian advantage.

Early sellers carried it on their heads in the morning. They balanced bamboo baskets through Little India’s streets. Some modern shops now make colored versions for special events.

Ananda Bhavan: 95 Syed Alwi Rd

Gulab Jamun

These sweets came from North India but changed in Singapore. Local versions are smaller and denser. The sugar syrup has pandan flavor – a Southeast Asian touch. Some places add ground pistachios on top.

Early Indian sweet makers used local palm sugar sometimes. This created a different taste from Indian gulab jamun. Today’s versions balance Indian and local sweetness levels.

Moghul Sweet Shop: 48 Serangoon Rd, inside Little India Arcade

Appam

Not only did South Indian Tamil workers bring appam to Jaffna, where it became known as hoppers but they also brought it to Singapore.

The local version is sweeter than Indian appam. Cooks add pandan essence to the batter. They serve it with orange sugar instead of plain jaggery.

The coconut milk is always fresh here. In India, some places use dried coconut. Singapore’s humidity makes the appam crispier around the edges.

Madras New Woodlands: 14 Upper Dickson Rd

Kothu Prata

Tamil workers created this dish using leftover prata bread. In India, they make it with paratha. It’s also popular in Sri Lanka and known as kottu roti in Ella.

Singapore’s version is less spicy and often includes chicken. The egg is cooked differently here too.

The chopping style is unique to Singapore. Cooks use bigger metal spatulas than in India. The sound of chopping becomes part of the street food experience.

Casuarina Curry: 197 Upper Thomson Rd

Tips for Eating in Little India

- Most places open early. Go before 11 AM for the freshest bread.

- Many restaurants close between 3 PM and 6 PM.

- Weekends get super busy. Try going on weekdays.

- Always check if dishes are spicy before ordering.

- Most places take cash only.

- It’s normal to eat with your hands. You’ll get a sink to wash up.

- If you don’t want to eat with your hands it’s OK to ask for cutlery.

Best Times to Visit Little India

Breakfast is busy with workers getting their prata fix. Lunch crowds show up from 12-2 PM. Dinner starts late, usually after 7 PM. Many places stay open until midnight.

The best food experience happens during Deepavali (usually October or November). Food stalls pop up everywhere.

How to Get There

Take the MRT to Little India station on the Downtown Line. Or grab a taxi to Race Course Road. The food area spreads out from the Tekka Centre market.